The original Carnegie Institution press release can be read here.

Five new forms of silica under extreme pressures at room temperature have been discovered by a team of researchers utilizing the extreme-brightness x-ray beams from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science user facility. Their findings were published in Nature Communications.

Silicon dioxide, commonly called silica, is one of the most-abundant natural compounds and a major component of the Earth's crust and mantle. It is well-known even to non-scientists in its quartz crystalline form, which is a major component of sand in many places. It is used in the manufacture of microchips, cement, glass, and even some toothpaste.

Silica's various high-pressure forms make it an often-used study subject for scientists interested in the transition between different chemical phases under extreme conditions, such as those mimicking the deep Earth.

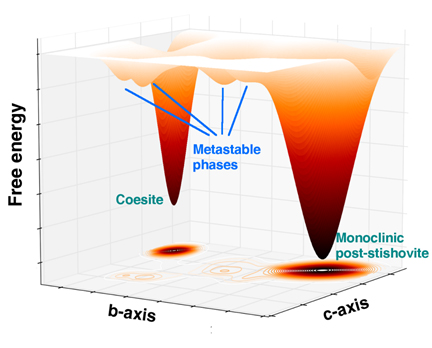

The first-discovered high-pressure, high-temperature denser form, or phase, of silica is called coesite, which, like quartz, consists of building blocks of silicon atoms surrounded by four oxygen atoms. Under greater pressures and temperatures, it transforms into an even denser form called stishovite, with silicon atoms surrounded by six oxygen atoms. The transition between these phases was crucial for learning about the pressure gradient of the deep Earth and the four-to-six configuration shift has been of great interest to geoscientists. Experiments have revealed even higher-pressure phases of silica beyond these two, sometimes called post-stishovite.

A structural phase is a distinctive and uniform configuration of the molecules that make up a substance. Changes in external conditions, such as temperature and pressure, can induce a transition from one phase to another, not unlike water freezing into ice or boiling into steam.

The team, including researchers from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research (China), and George Mason University carried out multiple x-ray diffraction experiments on coesite single crystals. The experiments were performed at x-ray beamlines 16-ID-B and 16-BM-D of the High-Pressure Collaborative Access Team (HP-CAT) at the Argonne Advanced Photon Source.

The team’s experiments at HP-CAT demonstrated that under a range from 257,000 to 523,000 times normal atmospheric pressure (26 to 53 gigapascals), a single crystal of coesite transforms into four new, co-existing crystalline phases before finally recombining into a single phase that is denser than stishovite, sometimes called post-stishovite, which is the team's fifth newly discovered phase. This transition takes place at room temperature, rather than the extreme temperatures found deep in the earth.

Scientists previously thought that this intermediate phase was amorphous, meaning that it lacked the long-range order of a crystalline structure. This new study uses superior x-ray analytical probes to show otherwise--they are four, distinct, well-crystalized phases of silica without amorphization. Advanced theoretical calculations performed by the team provided detailed explanations of the transition paths from coesite to the four crystalline phases to post-stishovite.

"Scientists have long debated whether a phase exists between the four- and six-oxygen phases," said article lead author Ho-Kwang “Dave” Mao. "These newly discovered four transition phases and the new phase of post-stishovite we discovered show the missing link for which we've been searching."

See: Q.Y. Hu1,2,3, J.-F. Shu3, A. Cadien2, Y. Meng3, W.G. Yang1,3, H.W. Sheng1,2*, and H.-K. Mao1,3**, “Polymorphic phase transition mechanism of compressed coesite,” Nat. Commun.6, 6630 (20 March 2015).DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7630

Author affiliations: 1Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research (China), 2George Mason University, 3Carnegie Institution of Washington, 4Carnegie Institution

Correspondence: *[email protected], **[email protected]

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant No. DMR-0907325. HP-CAT operations are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)-National Nuclear Security Administration under Award No. DE-NA0001974 and DOE-Basic Energy Sciences under Award No. DE-FG02-99ER45775, with partial instrumentation funding by the NSF. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.