The UT Southwestern Medical Center press release by Deborah Wormser can be read here.

Researchers from Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) at the University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center have uncovered a mechanism that a type of pathogenic bacteria found in shellfish use to sense when they are in the human gut, where they release toxins that cause food poisoning. The researchers used the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, to study Vibrio parahaemolyticus, a globally spread, Gram-negative bacterium that contaminates shellfish in warm saltwater during the summer. The bacterium thrives in coastal waters and is the world's leading cause of acute gastroenteritis.

"During recent years, rising temperatures in the ocean have contributed to this pathogen's worldwide dissemination," said Kim Orth, HHMI investigator and Professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry at UT Southwestern and senior author of the study, published in the online journal eLife.

About a dozen Vibrio species cause infection in humans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus is one of the three most common culprits. Vibrio infections cause an estimated 80,000 illnesses and 100 deaths in the United States every year.

The study found that two proteins made by Vibrio parahaemolyticus form an obligate heterodimer and work together to detect and capture bile salts in the intestines of people who eat raw or undercooked seafood containing the bacteria.

"When a person eats, acids in the stomach help break down the meal, and bile salts in the intestine aid in the solubilization of fatty food. When humans eat raw or undercooked shellfish contaminated with Vibrio parahaemolyticus, the bacteria use those same bile salts as a signal to release toxins," said Orth.

Evidence is increasing that several bacterial pathogens that cause gastrointestinal illness, including the extremely toxic Vibrio cholerae, sense bile salts. But until now, the mechanism that those pathogens use for doing this has remained unknown, Orth said. “In previous studies, only one bacterial gene had been implicated in receiving and transmitting the gut-sensing signal.”

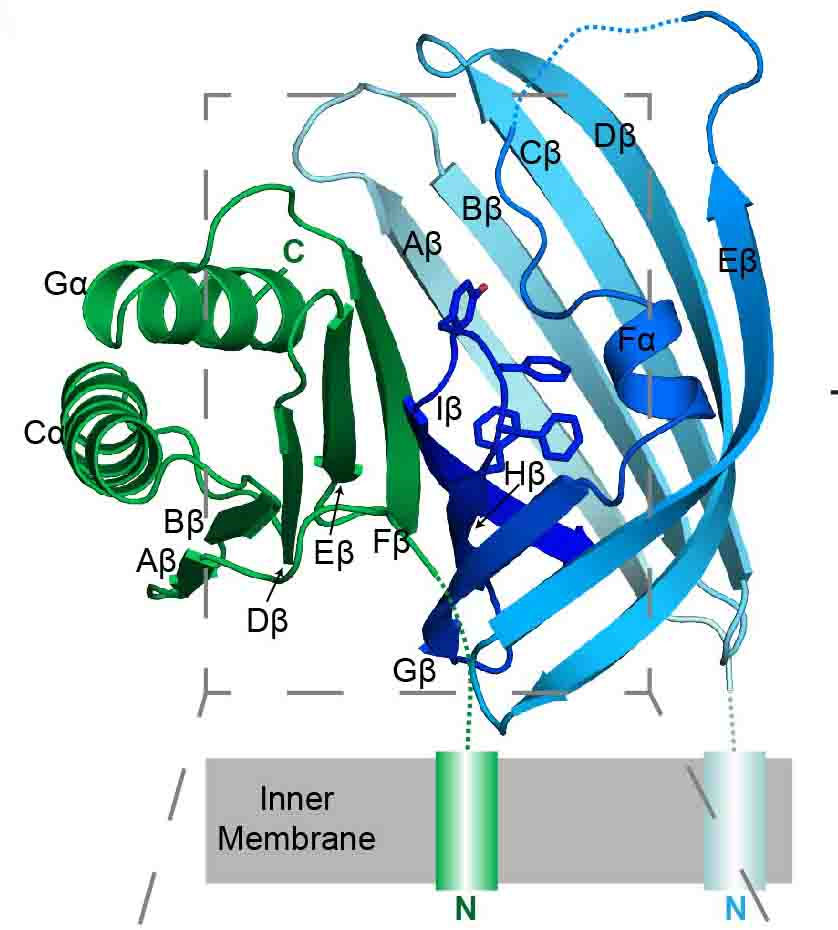

"We discovered that not one, but two genes are required for Vibrio to receive the bile salt signal. These genes encode two proteins that form a complex on the surface of the bacterial membrane. Using x-ray crystallography [at the Structural Biology Center Collaborative Access Team 19-ID-D beamline at the APS], we found that these proteins create a barrel-like structure that binds bile salts and receives the signal to tell the bacterial cell to start making toxins," she said.

Future experiments will aim to understand how binding of bile salt by this protein complex induces the release of toxins.

"Ultimately, we want to understand how other pathogenic bacteria sense environmental cues to produce toxins. With this knowledge, we might be able to design pharmaceuticals that could prevent toxin production, and ultimately avoid the damaging effects of infections," she said.

The receptor pair could possibly act as a model to discover sensors in other bacteria where pharmaceuticals might be more applicable, Orth said, adding "we are in the early stages of this research."

(Note: A video showing the rotation of the VtrA/VtrC heterodimer can be seen here.)

See: Peng Li, Giomar Rivera-Cancel, Lisa N. Kinch, Dor Salomon, Diana R. Tomchick, Nick V. Grishin, Kim Orth*, “Bile salt receptor complex activates a pathogenic type III secretion system,” eLife 5, e15718 (2016). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.15718

Author affiliation: HHMI, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Correspondence: *[email protected]

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-AI087808, (K.O) and R01-GM094575 (N.V.G.), Welch Research Foundation Grants I-1561 (K.O.) and I-1505 (N.V.G.). The Structural Biology Center at the APS is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov