The original University of Utah press release by Lisa Potter can be read here.

Scientists have solved a decade-long puzzle about lithium, an essential metal in cellphone and computer batteries. Using extreme-pressure experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) and powerful supercomputing, an international team has unraveled the mystery of a fundamental property of lithium. Its atoms are arranged in a simple structure, and may be the first direct evidence of a quantum solid behavior in a metal.

Until now, all previous experiments have indicated that lithium’s atoms had a complex arrangement. The idea baffled theoretical physicists. With only three electrons, lithium is the lightest, simplest metal on the periodic table and should have a simple structure to match.

The new study, published in Science, combined theory and experimentation to discover the true structure of lithium at cold temperatures, in its lowest energy state.

Scientists suggest that rapid cooling led lithium atoms to arrange themselves in complex structure and resulted in misinterpretation of the previous experimental results. To avoid this, Shanti Deemyad, associate professor at the University of Utah who led the experimental aspect of the study, applied extreme pressure to the lithium before cooling down the samples.

Deemyad’s research group prepared the lithium samples in tiny pressure cells at the University of Utah. The group then traveled to the Argonne National Laboratory (APS), an Office of Science user facility, to apply pressure up to 10,000 times the Earth’s atmosphere by pressing the sample between the tip of two diamonds. They then cooled and depressurized the samples. They examined the structures at low pressure and temperature using high-brightness x-ray beams from the High Pressure Collaborative Access Team (HP-CAT) 16-ID-B beamline at the APS.

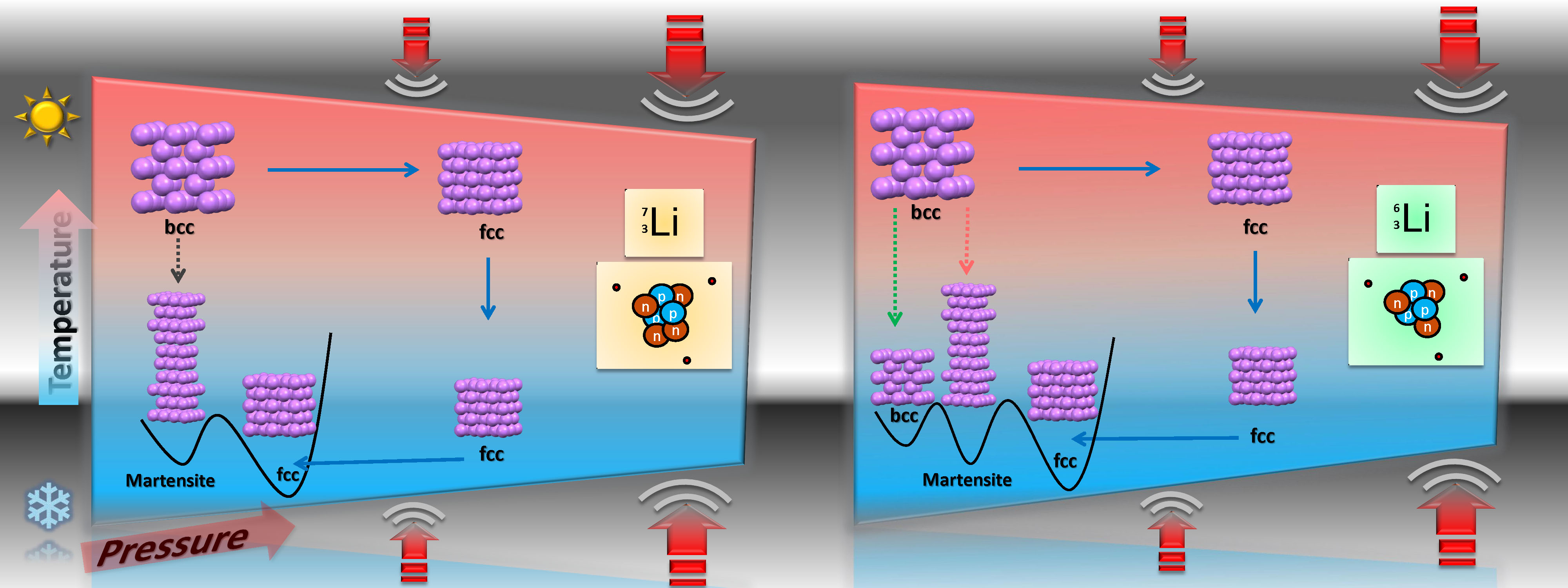

The researchers looked at two isotopes of lithium — the lighter lithium 6 and heavier lithium 7. They found that the lighter isotope behaves differently in its transitions to lower energy structures under certain thermodynamic paths than the heavier isotope, a behavior previously only seen in helium. The difference means that depending on the weight of the nuclei, there are different ways to get to the lower energy states. This is a quantum solid characteristic.

Graeme Ackland, professor from the University of Edinburgh, led the theoretical aspect of the study by running the most sophisticated calculations of lithium’s structure to date, using advanced quantum mechanics on the ARCHER supercomputer. Both experimentation and theoretical parts of the study found that lithium’s lowest energy structure is not complex or disordered, as previous results had suggested. Instead, its atoms are arranged simply, like oranges in a box.

Corresponding author Deemyad of the University of Utah Department of Physics & Astronomy, said: “Our experiments revealed that lithium is the first metallic element with quantum lattice structure behavior at moderate pressures. This will open up new possibilities for rich physics.”

Co-author Miguel Martinez-Canales of the University of Edinburgh School of Physics and Astronomy, said: “Our calculations needed an accuracy of one in 10 million, and would have taken over 40 years on a normal computer.”

Lead theoretical author Graeme Ackland of the University of Edinburgh School of Physics and Astronomy, said: “We were able to form a true picture of cold lithium by making it using high pressures. Rather than forming a complex structure, it has the simplest arrangement that there can be in nature.”

See: Graeme J. Ackland1, Mihindra Dunuwille2, Miguel Martinez-Canales1, Ingo Loa1, Rong Zhang2, Stanislav Sinogeikin3, Weizhao Cai2, and Shanti Deemyad2*, “Quantum and isotope effects in lithium metal,” Science 356, 1254 (2017). DOI: 10.1126/science.aal4886

Author affiliations: 1University of Edinburgh, 2University of Utah, 3Carnegie Institution of Washington

Correspondence: *[email protected]

HP-CAT operations are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)-National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) under award DE-NA0001974 with partial instrumentation funding by the National Science Foundation (NSF). Beam time for these experiments was provided by the Carnegie-DOE Alliance Center, which is supported by DOE-NNSA under grant DE-NA-0002006. Research at the University of Utah was supported by the NSF Division of Materials Research award 1351986. S.S. acknowledges the support of the DOE-Basic Energy Sciences/ Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under award DE-FG02-99ER45775. Research at the University of Edinburgh is supported by EPSRC with computing time on EPCC’s ARCHER supercomputer (UKCP grant K01465X). G.J.A. was supported by an ERC fellowship “Hecate” and a Royal Society Wolfson fellowship. This work also used resources provided by the Edinburgh Compute and Data Facility [ECDF, www.ecdf.ed.ac.uk; the ECDF is partially supported by the eDIKT initiative (www.edikt.org.uk)]. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

On a related topic, see: S.F. Elatresh, W. Cai, N.W. Ashcroft, R. Hoffmann, S. Deemyad, and S.A. Bonev, “Evidence from Fermi surface analysis for the low-temperature structure of lithium,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114(21), 5389 (2017).

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.