The original University of Notre Dame press release by Jessica Sieff can be read here.

Utilizing a range of experimental tools, including high-brightness x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), a research team from the University of Notre Dame, Purdue University, and Cummins Inc. discovered a catalytic process that could help curb emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) from diesel-powered vehicles, a priority air pollutant that is a key ingredient in smog.

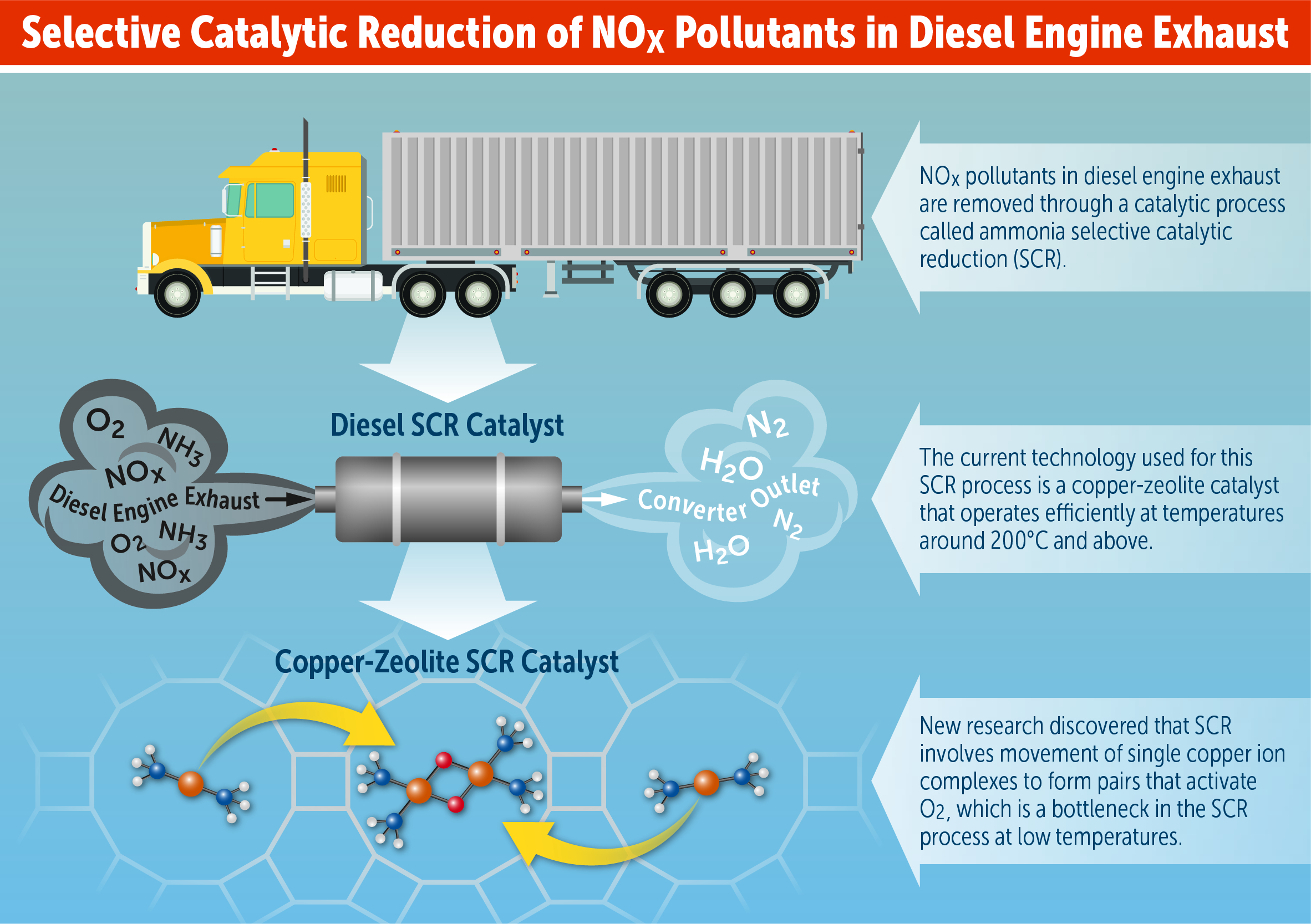

Current emission regulations and control systems for diesel engines have reduced pollution at high temperatures. While motorists around the world wait for their vehicles to warm up, a majority of NOx emissions – between 70% and 80% – take place during transient and cold-start conditions, impairing air quality.

The study, published in the journal Science, is the culmination of a decade of collaborative research by the team, funded by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, according to William Schneider, co-author of the study.

“Diesel engines power virtually all heavy-duty trucks, and NOx emissions control remains one of the key challenges facing manufacturers and operators,” said Schneider, Professor of Engineering in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at Notre Dame.

Schneider led the Notre Dame team and focused on copper-exchanged zeolites, a particular class of catalysts used to promote the conversion of NOx into environmentally benign nitrogen gas. These catalysts “light off,” or begin functioning, at temperatures too high to capture a large fraction of the NOx produced.

“The key challenge in reducing emissions is that they can occur over a very broad range of operating conditions, and especially exhaust temperatures,” said Rajamani Gounder, the Larry and Virginia Faith Assistant Professor of Chemical Engineering in Purdue University’s Davidson School of Chemical Engineering. “Perhaps the biggest challenge is related to reducing NOx at low exhaust temperatures, for example during cold start or in congested urban driving.”

The researchers discovered the key chemical step that limits the performance of these catalysts at low temperature.

“We knew that copper ions trapped in the zeolite pores were responsible for the catalytic reaction, but we did not know what caused the chemical reaction to slow to such an extent at lower temperatures,” Schneider said. The team developed sophisticated computer models, performed on supercomputers at Notre Dame’s Center for Research Computing and the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, to track the movement of the copper ions within the zeolite pores. They discovered that the ions were much more mobile than anyone had appreciated, so much so that they were able to swim through the zeolite pores and pair up.

“We hypothesized that this pairing was key to the low-temperature performance,” said Schneider. X-ray absorption spectroscopy experiments performed by the team at the Materials Research Collaborative Access Team (MR-CAT) 10-ID-B x-ray beamline of the Argonne National Laboratory APS proved that this pairing was indeed happening during one step in the overall catalytic process.

“To make these discoveries, we needed to use techniques, such as x-ray absorption spectroscopy, that could ‘see’ the copper atoms while the catalytic reaction was happening,” said Jeffrey Miller, Professor of Chemical Engineering in Purdue University’s Davidson School of Chemical Engineering.

The team was able to combine the experiments and computations to quantify the pairing and its influence on NOx removal.

“This is a goal that the catalysis community has been striving toward for many years,” said Schneider. “This information paves the way to developing catalysts that outperform current formations at lower temperatures, allowing diesel engines to meet stringent emissions regulations. Further, we think we can take advantage of the pairing process for other catalytic reactions beyond NOx removal.”

See: Christopher Paolucci1, Ishant Khurana2, Atish A. Parekh2, Sichi Li1, Arthur J. Shih2, Hui Li1, John R. Di Iorio2, Jonatan D. Albarracin-Caballero2, Aleksey Yezerets3, Jeffrey T. Miller2, W. Nicholas Delgass2, Fabio H. Ribeiro2, William F. Schneider1*, and Rajamani Gounder2**, “Dynamic multinuclear sites formed by mobilized copper ions in NOx selective catalytic reduction,” Science, published on line 17 August 2017. DOI: 10.1126/science.aan5630

Author affiliations: 1University of Notre Dame, 2Purdue University, 3Cummins, Inc.

Correspondence: *[email protected], **[email protected]

Financial support was provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF) GOALI program under award number 1258715-CBET (Purdue) and 1258690-CBET (Notre Dame); the NSF Faculty Early Career Development Program under award number 1552517-CBET (R.G.); Cummins, Inc. (I.K, A.S., A.P., J.A.C.); and The Patrick and Jane Eilers Graduate Student Fellowship for Energy Related Research (C.P.). We thank the Center for Research Computing at Notre Dame, and EMSL, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, for computational resources. MR-CAT operations are supported by the U.S. DOE and the MR-CAT member institutions. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.