The original Washington University in St. Louis press release by Diana Lutz can be read here.

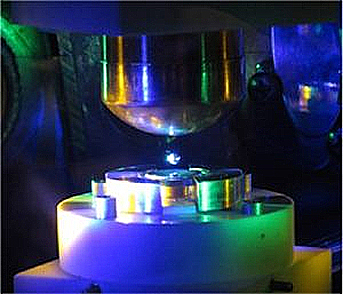

For the most part, scientists have been able to measure only bulk properties of glass-forming liquids, such as viscosity and specific heat, and the interpretations they came up with depended in part on the measurements they took. The glass literature is notoriously full of contradictory findings, and workshops about glass are the venue for lively debate. In the past 15 years, new experimental setups that scatter x-rays or neutrons off the atoms in a droplet of liquid that is held without a container (which would provoke it to crystallize) have allowed scientists at long last to measure the atomic properties of the liquid. And that is the level at which they suspect the secrets of the glass transition are hidden. The glass transition is arbitrarily defined as the point at which a liquid is too thick to flow and so meets the practical definition of a solid. In one such study, Ken Kelton (Washington University in St. Louis) and his research team (Chris Pueblo, of Washington University, and Minhua Sun, of Harbin Normal University in China) used the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’S) Advanced Photon Source to compare a measure of the interaction of atoms for different glass-forming liquids. Their results, published in Nature Materials, reconcile several measures of glass formation, a sign that they are on the right track.

“We have shown that the concept of fragile and strong liquids, which was invented to explain why viscosity changes in markedly different ways as a liquid cools, actually goes much deeper than just the viscosity,” Kelton said. “It is ultimately related to the repulsion between atoms, which limits their ability to move cooperatively. This is why the distinction between fragile and strong liquids also appears in structural properties, elastic properties and dynamics. They’re all just different manifestations of that atomic interaction.”

This is the first time the connection between viscosity and atomic interactions has been demonstrated experimentally, he said. Intriguingly, his studies and work by others suggest that the glass transition begins not at the conventional glass transition temperature but rather at a temperature approximately two times higher in metallic glasses (more than two times higher in the silicate glasses, such as window glass). It is at that point, Kelton said, the atoms first begin to move cooperatively.

Kelton’s latest discoveries follow earlier investigations of a characteristic of glass-forming liquids called fragility. To most people, all glasses are fragile, but to physicists some are “strong” and others are “fragile.”

The distinction was first introduced in 1995 by Austen Angell, a professor of chemistry at Arizona State University, who felt that a new term was needed to capture dramatic differences in the way a liquid’s viscosity increases as it approaches the glass transition.

The viscosities of some liquids change gradually and smoothly as they approach this transition. But as other liquids are cooled, their viscosity changes very little at first, but then takes off like a rocket as the transition temperature approaches.

At the time, Angell could only measure viscosity, but he called the first type of liquid “strong” and the second type “fragile” because he suspected a structural difference underlay the differences that he saw.

“It’s easier to explain what he meant if you think of a glass becoming a liquid rather than the other way around,” Kelton said. “Suppose a glass is heated through the glass transition temperature. If it’s a ‘strong’ system, it ‘remembers’ the structure it had as a glass—which is more ordered than in a liquid—and that tells you that the structure does not change much through the transition. In contrast, a ‘fragile’ system quickly ‘forgets’ its glass structure, which tells you that its structure changes a lot through the transition.

“People argued that the change in viscosity had to be related to the structure — through several intermediate concepts, some of which are not well defined,” Kelton added. “What we did was hop over these intermediate steps to show directly that fragility was related to structure.”

In 2014, he with members of his group published in Nature Communications the results of experiments that showed that the fragility of a glass-forming liquid is reflected in something called the structure factor, a quantity measured by scattering x-rays off a droplet of liquid that contains information about the position of the atoms in the droplet.

“It was just as Angell had suspected,” Kelton said. “The rate of atomic ordering in the liquid near the transition temperature determines whether a liquid is ‘fragile’ or ‘strong.'”

But Kelton wasn’t satisfied. Other scientists were finding correlations between the fragility of a liquid and its elastic properties and dynamics, as well as its structure. “There has to be something in common,” he thought. “What’s the one thing that could underlie all of these things?” The answer, he believed, had to be the changing attraction and repulsion between atoms as they moved closer together, which is called the atomic interaction potential.

If two atoms are well separated, Kelton explained, there is little interaction between them and the interatomic potential is nearly zero. When they get closer together, they are attracted to one another for a variety of reasons. The potential energy goes down, becoming negative (or attractive). But then as they move closer still, the cores of the atoms start to interact, repelling one another. The energy shoots way up.

“It’s that repulsive part of the potential we were seeing in our experiments,” Kelton said.

What they found when they measured the repulsive potential of 10 different metallic alloys at the X-ray Science Division 6-ID-D x-ray beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, is that “strong” liquids have steeper repulsive potentials and the slope of their repulsive potential changes more rapidly that of “fragile” ones.

“What this means,” Kelton said, “is that ‘strong’ liquids order more rapidly at high temperatures than ‘fragile’ ones. That is the microscopic underpinning of Angell’s fragility.

“What’s interesting,” Kelton continued, “is that we see atoms beginning to respond cooperatively — showing awareness of one another — at temperatures approximately double the glass transition temperature and close to the melting temperature.

“That’s where the glass transition really starts,” he said. “As the liquid cools more and more, atoms move cooperatively until rafts of cooperation extend from one side of the liquid to the other and the atoms jam. But that point, the conventional glass transition, is only the end point of a continuous process that begins at a much higher temperature.”

See: Christopher E. Pueblo1, Minhua Sun1,3, and K. F. Kelton1*, “Strength of the repulsive part of the interatomic potential determines fragility in metallic liquids,” Nat. Mater. 16, 792 (2017). DOI: 10.1038/nmat4935

Author affiliations: 1Washington University in St Louis, 2Harbin Normal University

Correspondence: *[email protected]

See also: N.A. Mauro, M. Blodgett, M.L. Johnson, A.J. Vogt, and K.F. Kelton, "A structural signature of liquid fragility," Nat. Commun. 5, 4616-1-4616-7 (2014). DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5616

We thank D. Robinson for his assistance with the high-energy x-ray diffraction studies at the Advanced Photon Source. K.F.K. and C.E.P. gratefully acknowledge support by NASA under Grant No. NNX16AB52G and the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DMR 15-06553. M.S. gratefully acknowledges support by the Foundation for the Science and Technological Innovation Talent of Harbin (No. 2010RFQXG028). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.