The original University of Southern California press release can be read here.

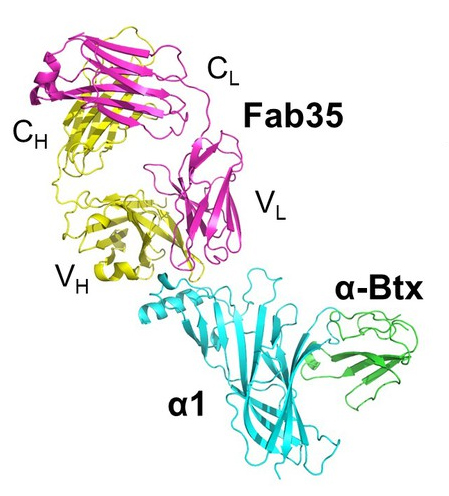

An estimated 36,000 to 60,000 Americans (around 20 per every 100,000) are affected by myasthenia gravis each year. At least, that is the estimated number of patients who receive the diagnosis. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America believes far more have the disease but they are not diagnosed. Diagnosed patients may end up on therapies that treat one or some of the symptoms -- but not the disease itself. The symptoms may range from weakness in the facial muscles and eyes to slurred speech. Kaori Noridomi, a researcher in Lin Chen's Molecular and Computational Biology lab at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences and her team carried out research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Advanced Photon Source. They developed a three-dimensional crystal structure of the disease's molecular interactions with a neural receptor that is the regular target of the disease. It is the first high-resolution visual display of the molecular interactions.

Chen, Noridomi, and their team noted in the study, published in eLife, that myasthenia gravis is “the first, and so far, only autoimmune disease with a well-defined autoantigen target,” alluding to the “nicotinic acetylcholine receptors” that the disease's malfunctioning antibodies attack.

These are the same kind of receptors that respond to drugs such as nicotine. In the muscles, though, these receptors have a specific job: receive and transmit the brain's orders to contract muscles.

The brain sends those orders in the form of a chemical neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, directing it to the receptors on the skeletal muscles. In a healthy body, once the acetylcholine reaches the receptors on the destined muscle or muscles, it binds with them and causes them to contract.

In a patient with myasthenia gravis, the disease's antibodies jam this process, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The antibodies attack the receptor and try to destroy a protein within it, according to the study.

The crystal structure was determined at the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute (GM/CA-XSD) 23-ID-B x-ray beamline at the Argonne National Laboratory APS (the APS is an Office of Science user facility.) The structure gives scientists a clear view of how exactly the disease behaves and interferes with brain-to-muscle signals. The ability to see these interactions will likely accelerate research of the disease and could possibly lead to new disease-targeting therapies, said Chen, the study's corresponding author and a USC Dornsife College professor of biological sciences and chemistry.

“Because of this finding, we may also find a better quantitative way to identify patients,” Chen said.

Myasthenia gravis is most frequently diagnosed by detection of those distinct, rogue antibodies. Scientists first identified myasthenia gravis as a condition in 1877. The USC scientists noted that the disease's pathology wasn't understood until the 1970s when researchers realized that disease's antibodies were, for the most part, attacking a specific receptor in the muscles.

With the crystal model, the scientists were able to see the disease's interactions with the receptor as if it were frozen as a moment in time. They also saw that it had cross-linked with several receptors to accelerate the degradation of their proteins.

“Our studies suggest it is possible to develop drug molecules to inhibit the binding of a large fraction of MG antibodies to the receptor,” the scientists wrote.

However, scientists remain unsure why some patients experience more severe or widespread symptoms than others.

“It's a little bit of disease and a little bit of heredity that cause this,” Noridomi said. “In some people, the level of symptoms may be so slight and varied that they may not even go to the trouble of finding out if they have a disease. By that, I mean, maybe they just don't feel good one day, like they don't feel like going to work. They don't know that ultimately they are suffering an attack.”

Noridomi said she believes the team's findings will lead to greater scientific understanding and may give patients long-awaited hope.

See: Kaori Noridomi, Go Watanabe, Melissa N Hansen, Gye Won Han, and Lin Chen*, “Structural insights into the molecular mechanisms of myasthenia gravis and their therapeutic implications,” eLife 6, e23043 (2017). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.23043

Author affiliation: University of Southern California

Correspondence: *[email protected]

We would like to thank the GM/CA staff members, especially Ruslan Sanishvili, for help with data collection. This work was supported in part by US National Institutes of Health grants, R01 GM064642 (LC) and R01 AI113009 (LC). GM/CA-XSD has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006). The Eiger 16M detector was funded by an NIH–Office of Research Infrastructure Programs, High-End Instrumentation Grant (1S10OD012289-01A1). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.