Scientists have uncovered a great deal about the Earth’s solid inner core, but many mysteries still surround our planet’s deep interior. The major element in the core is iron, but the exact crystal form of this element continues to be debated. Also uncertain is the identity and quantity of light elements that are likely alloyed with iron in the core. Laboratory experiments on candidate core materials have generally focused on a specific crystal form of iron called hexagonal close-packed (hcp), but recent theoretical evidence has shown that pure hcp iron may not be able to explain some seismic observations. A new study looks at an alternative possibility: body-centered cubic (bcc) iron and its alloy with silicon. Using the high-brightness x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), researchers measured for the first time the sound speed of bcc iron at high temperature and pressure simultaneously. When compared with other observations, the new results suggest that bcc iron alloy could be a core constituent.

Much of our knowledge about the Earth’s core has come from studying seismic waves that pass through the center of the planet. A puzzling aspect about these waves is that they travel about 3% to 4% faster in the direction along the Earth’s rotation axis than in the plane of the equator. The current understanding of this seismic wave anisotropy is that crystals in the inner core are preferentially aligned in such a way that the core materials display elastic anisotropy. This elasticity affects the sound speed at which seismic waves propagate. However, the elasticity of hcp iron crystals – which are thought to be the most stable iron phase in the extreme environment of the core – is fairly constant (or isotropic) with respect to direction. By contrast, bcc iron crystals exhibit a large elastic anisotropy (as high as 30%), so one plausible hypothesis is that a fraction of the core is made up of bcc iron, with the rest being perhaps hcp iron.

In order to validate this possibility, geologists need more data on bcc iron. Previously, ultrasonic studies of bcc iron have measured its sound speed and other properties at high temperature, but not at high pressure. Scientists from the University of Texas at Austin, Argonne National Laboratory, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have now investigated bcc iron simultaneously at high temperatures and pressures. They also performed high-pressure, room-temperature measurements on a bcc iron alloy containing 8% silicon by weight. Using an externally-heated diamond anvil cell, the team was able to heat samples to temperatures as high as 700 Kelvin (330° C), while squeezing them to pressures as high as 11 gigapascals (100,000 atmospheres).

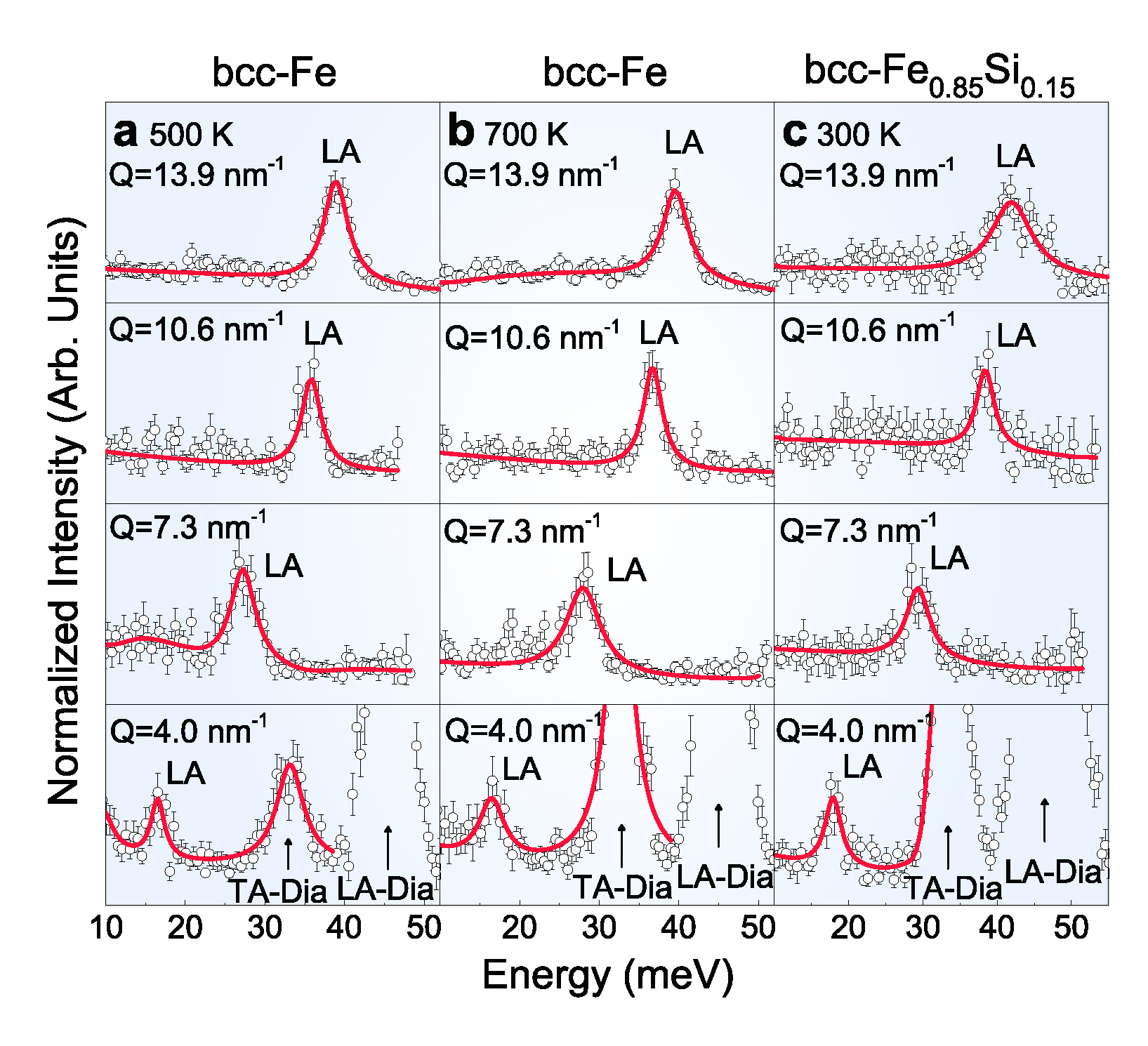

To probe the iron under these extreme conditions, the researchers used synchrotron radiation from the HERIX (high-energy resolution inelastic x-ray scattering) instrument at the X-ray Science Division 3-ID-C beamline at the Argonne APS (an Office of Science user facility) and recorded the results, as reported in the journal of Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. The HERIX data showed peaks (see the figure) that correspond to x-ray photons interacting with iron crystal phonons (i.e., quantized sound waves). Analysis of the HERIX spectra allowed the researchers to derive the sound speed at different temperatures and pressures. They also measured the density of their samples using in situ x-ray diffraction measurements.

By combining their data, the researchers showed that the sound speed of bcc iron decreases by about 1% as the temperature increases from 300 to 700 Kelvin. A similar drop in sound speed was recently found for hcp iron. If this velocity reduction continues at higher temperatures like those in the core, then the sound speed of pure iron may be too low to explain seismic wave observations.

One way to offset the temperature effect would be to include more light elements, like silicon. The research team showed that the sound speed of their iron-silicon alloy is 1-2% higher than pure bcc iron.

Of course, these measurements are all taken at temperatures and pressures that are far below those in the core (5000 Kelvin and 350 gigapascals). But the authors argue that trends in their data and the data from previous studies imply that the sound speed and elastic anisotropy of bcc iron alloy could help explain seismic wave observations. — Michael Schirber

See: Jin Liu1*, Jung-Fu Lin1, Ahmet Alatas2, Wenli Bi2,3, “Sound velocities of bcc-Fe and Fe0.85Si0.15 alloy at high pressure and Temperature,” Phys. Earth Planet. In. 233, 24 (2014). DOI: 10.1016/j.pepi.2014.05.008

Author affiliations: 1University of Texas at Austin, 2Argonne National Laboratory, 3University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Correspondence: * [email protected]

J. F. Lin acknowledges support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (EAR-1053446 and EAR-1056670) and the Carnegie/DOE Alliance Center. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Earth figure: "Earth poster" by Kelvinsong - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Earth_poster.svg#mediaviewer/Fi…

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.