The original Tufts University press release by Patrick Collins can be read here.

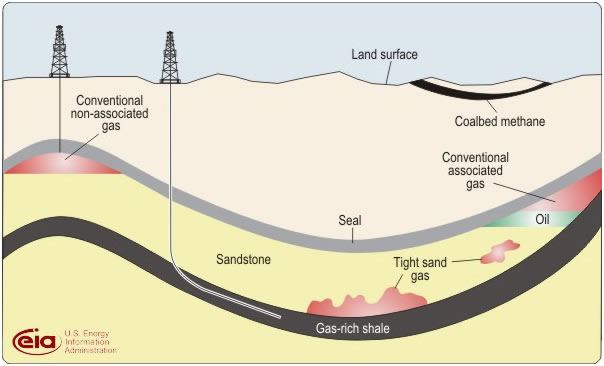

Methane in shale gas can be turned into hydrocarbon fuels using an innovative platinum and copper alloy catalyst, according to new research carried out in part at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory.

Platinum or nickel are known to break the carbon-hydrogen bonds in methane found in shale gas to make hydrocarbon fuels and other useful chemicals. However, this process causes “coking” – the metal becomes coated with a carbon layer rendering it ineffective by blocking reactions from happening at the surface.

The new alloy catalyst is resistant to coking, so it retains its activity and requires less energy to break the bonds than other materials. Currently, methane reforming processes are extremely energy intense, requiring temperatures of about 900 degrees Celsius. This new material could lower this to 400 degrees Celsius, saving energy.

The study, led by researchers from University College London (UCL) and Tufts University with Argonne and published in Nature Chemistry, demonstrates the benefits of the new highly diluted alloy of platinum in copper – a single atom alloy – in making useful chemicals from small hydrocarbons.

A combination of surface science, in situ x-ray absorption spectroscopy studies at the X-ray Science Division x-ray beamline 12-BM at the APS, an Office of Science user facility, catalysis experiments, and powerful computing techniques were used to investigate the performance of the alloy. These showed that the platinum breaks the carbon-hydrogen bonds, and the copper helps couple hydrocarbon molecules of different sizes, paving the way towards conversion to fuels.

Study co-lead author, Professor Michail Stamatakis (UCL Chemical Engineering), said, “We used supercomputers to model how the reaction happens – the breaking and making of bonds in small molecules on the catalytic alloy surface, and also to predict its performance at large scales. For this, we needed access to hundreds of processors to simulate thousands of reaction events.”

While UCL researchers traced the reaction using computers, Tufts University chemists and chemical engineers ran surface science and micro-reactor experiments to demonstrate the viability of the new catalyst – atoms of platinum dispersed in a copper surface – in a practical setting. They found the single atom alloy was very stable and only required a tiny amount of platinum to work.

The study’s lead, Professor Charles Sykes of the Department of Chemistry in Tufts University’s School of Arts & Sciences, said, “Seeing is believing, and our scanning-tunneling microscope allowed us to visualize how single platinum atoms were arranged in copper. Given that platinum is over $1,000 an ounce, versus copper at 15 cents, a significant cost saving can be made.”

Together, the team shows that less energy is needed for the alloy to help break the bonds between carbon and hydrogen atoms in methane and butane, and that the alloy is resistant to coking, opening up new applications for the material.

The study’s co-lead author, Distinguished Professor Maria Flytzani-Stephanopoulos of the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering in Tufts University’s School of Engineering, said, “While model catalysts in surface science experiments are essential to follow the structure and reactivity at the atomic scale, it is exciting to extend this knowledge to realistic nanoparticle catalysts of similar compositions and test them under practical conditions, aimed at developing the catalyst for the next step – industrial application.”

The team now plans on developing further catalysts that are similarly resistant to the coking that plagues metals traditionally used in this and other chemical processes.

See: Matthew D. Marcinkowski1, Matthew T. Darby2, Jilei Liu1, Joshua M. Wimble1, Felicia R. Lucci1, Sungsik Lee3, Angelos Michaelides2, Maria Flytzani-Stephanopoulos1*, Michail Stamatakis2**, and E. Charles H. Sykes1***, “Pt/Cu single-atom alloys as coke-resistant catalysts for efficient C–H activation,” Nat. Chem. Advance online publication, 8 January 2018. DOI: 10.1038/NCHEM.2915

Author affiliations: 1Tufts University, 2University College London, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *[email protected], **[email protected], ***[email protected]

All surface science studies (M.D.M., F.R.L. and E.C.H.S.) were performed with support from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences CPIMS Program, under grant no. FG02-10ER16170. J.L. and M.F-S. acknowledge the U.S. DOE (DE-FG02-05ER15730) for financial support of the catalysis work. M.T.D is funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council UK as part of a Doctoral Training Grant (Award Ref. 1352369). The authors acknowledge the use of the UCL High Performance Computing Facilities (Legion@UCL and Grace@UCL) and associated support services, in the completion of the computational part of this work. The theoretical portion of the research also used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which is a DOE Office of Science user facility supported under contract no. DE-AC05-00OR22725. Access to the Oak Ridge facility was provided via the Integrated Mesoscale Architectures for Sustainable Catalysis (IMASC), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences under award #DE-SC0012573. A.M. is supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)–European Research Council grant agreement no. 616121 (HeteroIce project). A.M. is also supported by the Royal Society through a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.