The original Rice University press release by Mike Williams can be read here.

Some materials are like people. Let them relax in the sun for a little while and they perform a lot better. A collaboration carrying out research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) found that to be the case with a perovskite compound touted as an efficient material to collect sunlight and convert it into energy.

The researchers from Los Alamos National Laboratory, Rice University, Purdue University, Northwestern University, Université de Rennes (France), and Argonne National Laboratory were led by Aditya Mohite, a staff scientist at Los Alamos who will soon become a professor at Rice University; Wanyi Nie, also a staff scientist at Los Alamos; and lead author and Rice graduate student Hsinhan (Dave) Tsai. They discovered that constant illumination relaxes strain in perovskite’s crystal lattice, allowing it to uniformly expand in all directions.

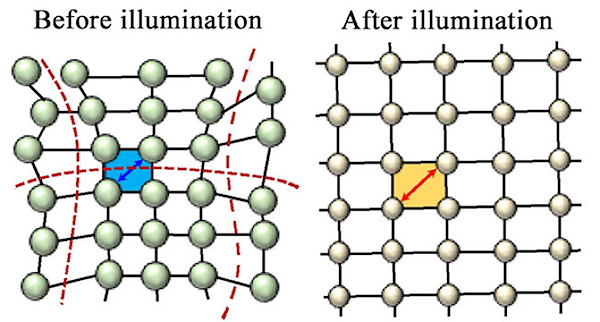

Expansion aligns the material’s crystal planes and cures defects in the bulk. That in turn reduces energetic barriers at the contacts, making it easier for electrons to move through the system and deliver energy to devices.

This not only improves the power conversion efficiency of the solar cell, but also does not compromise its photostability, with negligible degradation over more than 1,500 hours of operation under continuous one-sun illumination of 100 milliwatts per cubic centimeter.

The research, which appeared in the journal Science, represents a significant step toward stable perovskite-based solar cells for next generation solar-to-electricity and solar-to-fuel technologies, according to the researchers.

“Hybrid perovskite crystal structures have a general formula of AMX3, where A is a cation, M is a divalent metal and X is a halide,” Mohite said. “It’s a polar semiconductor with a direct band gap similar to that of gallium arsenide.

“This endows perovskites with an absorption coefficient that is nearly an order of magnitude larger than gallium arsenide (a common semiconductor in solar cells) across the entire solar spectrum,” he said. “This implies that a 300-nanometer thick film of perovskites is sufficient to absorb all the incident sunlight. By contrast, silicon is an indirect band gap material that requires 1,000 times more material to absorb the same amount of sunlight.”

Mohite said researchers have long sought efficient hybrid perovskites that are stable in sunlight and under ambient environmental conditions.

“Through this work, we demonstrated significant progress in achieving both of these objectives,” he said. “Our triple-cation-based perovskite in a cubic lattice shows excellent temperature stability at more than 100 degrees Celsius (212 degrees Fahrenheit).”

The researchers modeled and made more than 30 semiconducting, iodide-based thin films with perovskite-like structures: Crystalline cubes with atoms arranged in regular rows and columns. They measured their ability to transmit current and found that when soaked with light, the energetic barrier between the perovskite and the electrodes largely vanished as the bonds between atoms relaxed.

Working at the X-ray Science Division x-ray beamline 8-ID-E at the APS, an Office of Science user facility at Argonne, the team employed grazing incidence wide-angle x-ray scattering (GIWAXS) to map the structures of the films, and their structural transformation under in situ illumination. Besides offering access to a wide range of the scattering vector to probe down to interatomic length scales ( 0.2 nm), the GIWAXS instrument maintains a vacuum environment, controls the sample temperature, and allows access for the users’ solar simulator lamp. Additionally, the excellent resolution available at 8-ID-E allowed the effects of the strain relaxation to be seen not just in the expansion of the lattice but as a change in the width of the diffraction features.

They were surprised to see that the barrier remained quenched for 30 minutes after the light was turned off. Because the films were kept at a constant temperature during the experiments, the researchers were also able to eliminate heat as a possible cause of the lattice expansion.

Measurements showed the “champion” hybrid perovskite device increased its power conversion efficiency from 18.5 percent to 20.5 percent. On average, all the cells had a raised efficiency above 19 percent. Mohite said perovskites used in the study were 7 percent away from the maximum possible efficiency for a single-junction solar cell.

He said the cells’ efficiency was nearly double that of all other solution-processed photovoltaic technologies and 5 percent lower than that of commercial silicon-based photovoltaics. They retained 85 percent of their peak efficiency after 800 hours of continuous operation at the maximum power point, and their current density showed no photo-induced degradation over the entire 1,500 hours.

“This work will accelerate the scientific understanding required to achieve perovskite solar cells that are stable,” Mohite said. “It also opens new directions for discovering phases and emergent behaviors that arise from the dynamical structural nature, or softness, of the perovskite lattice.”

The lead researchers indicated the study goes beyond photovoltaics as it connects, for the first time, light-triggered structural dynamics with fundamental electronic transport processes. They anticipate it will lead to technologies that exploit light, force or other external triggers to tailor the properties of perovskite-based materials.

See: Hsinhan Tsai1,2, Reza Asadpour3, Jean-Christophe Blancon1, Constantinos C. Stoumpos4, Olivier Durand5, Joseph W. Strzalka6, Bo Chen2, Rafael Verduzco2, Pulickel M. Ajayan2, Sergei Tretiak1, Jacky Even5, Muhammad Ashraf Alam3, Mercouri G. Kanatzidis4, Wanyi Nie1*, and Aditya D. Mohite1,2**, “Light-induced lattice expansion leads to high-efficiency perovskite solar cells,” Science 360, 67 (2018). DOI: 10.1126/science.aap8671

Author affiliations: 1Los Alamos National Laboratory, 2Rice University, 3Purdue University, 4Northwestern University, 5Université de Rennes, 6Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *[email protected], **[email protected]

Work at Northwestern was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science (grant SC0012541, structure characterization). A.D.M. acknowledges support by Office of

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy grant DE-FOA-0001647-1544 for this work. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.