The original University of Chicago “uchicago news” article by Louise Lerner can be read here.

The original University of Chicago “uchicago news” article by Louise Lerner can be read here.

Researchers used the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) to help them invent an innovative way for different types of quantum technology to “talk” to each other using sound. The study, published in Nature Physics, is an important step in bringing quantum technology closer to reality.

Scientists are eyeing quantum systems, which tap the quirky behavior of the smallest particles, as the key to a fundamentally new generation of atomic-scale electronics for computation and communication. But a persistent challenge has been transferring information between different types of technology, such as quantum memories and quantum processors.

“We approached this question by asking: Can we manipulate and connect quantum states of matter with sound waves?” said senior study author David Awschalom, the Liew Family Professor with the Institute for Molecular Engineering and senior scientist at Argonne National Laboratory.

One way to run a quantum computing operation is to use “spins”—a property of an electron that can be up, down or both. Scientists can use these like zeroes and ones in today’s binary computer programming language. But getting this information elsewhere requires a translator, and scientists thought sound waves could help.

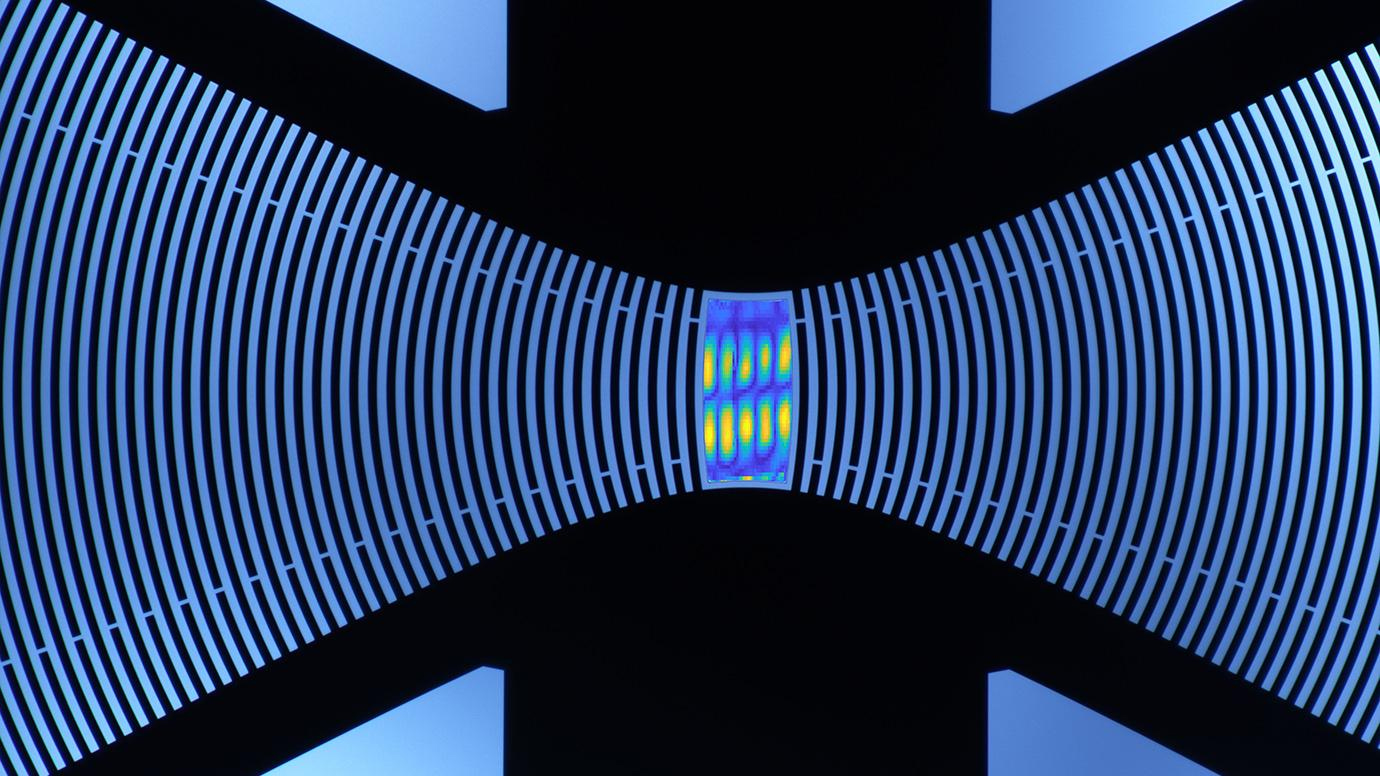

“The object is to couple the sound waves with the spins of electrons in the material,” said graduate student Samuel Whiteley, the co-first author on the Nature Physics paper. “But the first challenge is to get the spins to pay attention.” So they built a system with curved electrodes to concentrate the sound waves, like using a magnifying lens to focus a point of light.

The results were promising, but the researchers from The University of Chicago, and Argonne National Laboratory needed more data. To get a better look at what was happening, they worked with scientists at the Center for Nanoscale Materials (CNM) at Argonne to observe the system in real time. Essentially, they used extremely bright, powerful x-rays from the CNM/X-ray Science Division 26-ID-C x-ray beamline at the Advanced Photon Source as a microscope to peer at the atoms inside the material as the sound waves moved through it at nearly 7,000 kilometers per second. (Both the CNM and the APS are Office of Science user facilities at Argonne.)

“This new method allows us to observe the atomic dynamics and structure in quantum materials at extremely small length scales,” said Awschalom. “This is one of only a few locations worldwide with the instrumentation to directly watch atoms move in a lattice as sound waves passes through them.”

One of the many surprising results, the researchers said, was that the quantum effects of sound waves were more complicated than they’d first imagined. To build a comprehensive theory behind what they were observing at the subatomic level, they turned to Prof. Giulia Galli, the Liew Family Professor at the IME and a senior scientist at Argonne. Modeling the system involves marshalling the interactions of every single particle in the system, which grows exponentially, Awschalom said, “but Professor Galli is a world expert in taking this kind of challenging problem and interpreting the underlying physics, which allowed us to further improve the system.”

It’s normally difficult to send quantum information for more than a few microns, said Whiteley—that’s the width of a single strand of spider silk. This technique could extend control across an entire chip or wafer.

“The results gave us new ways to control our systems, and opens venues of research and technological applications such as quantum sensing,” said postdoctoral researcher Gary Wolfowicz, the other co-first author of the study.

The discovery is another from the University of Chicago’s world-leading program in quantum information science and engineering; Awschalom is currently leading a project to build a quantum “teleportation” network between Argonne and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory to test principles for a potentially un-hackable communications system.

The scientists pointed to the confluence of expertise, resources and facilities at the University of Chicago, Institute for Molecular Engineering and Argonne as key to fully exploring the technology.

“No one group has the ability to explore these complex quantum systems and solve this class of problems; it takes state-of-the-art facilities, theorists and experimentalists working in close collaboration,” Awschalom said. “The strong connection between Argonne and the University of Chicago enables our students to address some of the most challenging questions in this rapidly moving area of science and technology.”

See: Samuel J. Whiteley1, Gary Wolfowicz1,2, Christopher P. Anderson1, Alexandre Bourassa1, He Ma1, Meng Ye1, Gerwin Koolstra1, Kevin J. Satzinger1,3, Martin V. Holt4, F. Joseph Heremans1,4, Andrew N. Cleland1,4, David I. Schuster1, Giulia Galli1,4, and David D. Awschalom1,4*, “Spin–phonon interactions in silicon carbide addressed by Gaussian acoustics,” Nat. Phys., published on line 11 February 2019. DOI: 10.1038/s41567-019-0420-0

Author affiliations: 1The University of Chicago, 2Tohoku University, 3University of California, Santa Barbara, 4Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *[email protected]

The devices and experiments were supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research; material for this work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Use of the Center for Nanoscale Materials, an Office of Science user facility, was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. S.J.W. and K.J.S. were supported by the NSF GRFP, C.P.A. was supported by the Department of Defense through the NDSEG Program, and M.V.H., F.J.H., A.N.C., G.G. and D.D.A. were supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences. This work made use of the UChicago MRSEC (NSF DMR-1420709) and Pritzker Nanofabrication Facility, which receives support from the SHyNE, a node of the NSF’s National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NSF ECCS-1542205). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.