The original Northwestern University press release by Amanda Morris can be read here.

Northwestern University researchers have, for the first time, discovered a rare mineral hidden inside the teeth of a chiton, a large mollusk found along rocky coastlines. Before this strange surprise, the iron mineral, called santabarbaraite, only had been documented in rocks. The new finding, using data obtained at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) helps us understand how the whole chiton tooth, not just the ultrahard, durable cusp, is designed to allow them to chew on rocks to feed. Based on minerals found in chiton teeth, the researchers developed inks for three-dimensional (3-D) printing of bioinspired composites. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

“This mineral has only been observed in geological specimens in very tiny amounts and has never before been seen in a biological context,” said Northwestern’s Derk Joester, the study’s senior author. “It has high water content, gives it low density at relatively high strength. We think this might toughen the teeth without adding a lot of weight.”

One of the hardest known materials in nature, chiton teeth are attached to a soft, flexible, tongue-like radula (Fig. 1), which scrapes over rocks to collect algae and other food. Having long studied chiton teeth, Joester and his team most recently turned to Cryptochiton stelleri, a giant, reddish-brown chiton that is sometimes affectionately referred to as the “wandering meatloaf.”

To examine a tooth from Cryptochiton stelleri, Joester’s team collaborated with several x-ray beamline personnel at the APS (an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory) to use the facility’s high-brightness x-rays to carry out a variety of experiments.

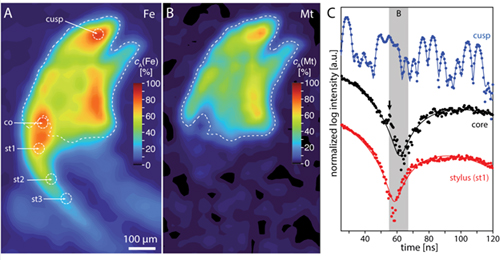

X-ray absorption spectro-microscopy at the iron K-edge was performed at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS x-ray microprobe beamline 13-ID-E where x-ray fluorescence maps were recorded to determine regions of interest for subsequent micro-x-ray near edge structure (µXANES) collection of XANES spectra.

Synchrotron x-ray computed microtomography was performed on the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team beamline 5-BM-C at the APS.

Synchrotron Mössbauer spectroscopy (SMS) (Fig. 2) was performed at the X-ray Science Division Inelastic X-ray and Nuclear Scattering Group's beamline 3-ID-B. “This kind of mineralogical mapping using the newly developed Mössbauer microscopy for the first time has allowed us to follow a biomineralization process," said co-author and APS senior scientist Ercan Alp, “producing interesting results. I expect more applications will follow.”

In addition, co-author Paul Smeets of Northwestern used transmission electron microscopy at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization and Experiment (NUANCE) Center.

The results showed that the rare santabarbaraite dispersed throughout the chiton’s upper stylus, a long, hollow structure that connects the head of the tooth to the flexible radula membrane.

“The stylus is like the root of a human tooth, which connects the cusp of our tooth to our jaw,” Joester said. “it is a tough material composed of extremely small santabarbaraite nanoparticles in a fibrous matrix made of biomacromolecules, similar to bones in our body.”

Joester’s group challenged itself to recreate this material in an ink designed for 3-D printing. Stegbauer developed a reactive ink comprising iron and phosphate ions mixed into a biopolymer derived from chitin. Along with Shay Wallace, a Northwestern graduate student in Mark Hersam’s laboratory, Stegbauer found that the ink printed well when mixed immediately before printing.

“As the nanoparticles form in the biopolymer, it gets stronger and more viscous. This mixture can then be easily used for printing. Subsequent drying in air leads to the hard and stiff final material,” Joester said.

Joester believes we can continue to learn from and develop materials inspired by the chiton’s stylus, which connects ultra-hard teeth to a soft radula.

“We’ve been fascinated by the chiton for a long time,” he said. “Mechanical structures are only as good as their weakest link, so it’s interesting to learn how the chiton solves the engineering problem of how to connect its ultrahard tooth to a soft underlying structure. This remains a significant challenge in modern manufacturing, so we look to organisms like the chiton to understand how this is done in nature, which has had a couple hundred million years of lead time to develop.”

See: Linus Stegbauer1, E. Ercan Alp2, Paul J. M. Smeets1, Robert Free1, Shay G. Wallace1, Mark C. Hersam1, and Derk Joester1*, “Persistent Polyamorphism in the Chiton Tooth: From a New Biomineral to Inks for Additive Manufacturing,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118(23), e202016011 (June 8 2021). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2020160118

Author affiliations: 1Northwestern University, 2Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *[email protected]

L.S. was supported by a research fellowship of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (STE2689/1-1). This work was in part supported by the National Science Foundation (DMR-1508399 and DMR-1905982). R.F. was supported by an F31 fellowship from the National Institutes of Health (NIH-DE026952). S.G.W. and M.C.H. acknowledge support from the Air Force Research Laboratory under agreement FA8650-15-2-5518. This work made use of the following core facilities operated by Northwestern University: MatCI; BioCryo, SPID, NUANCE and EPIC, which received support from the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN), the Keck Foundation, and the State of Illinois, through the IIN; IMSERC, QBIC, which received support NASA Ames Research Center NNA06CB93G. MatCI, BioCryo, SPID, NUANCE, and EPIC were further supported by the MRSEC program (NSF DMR-1720139) at the Materials Research Center; BioCryo, SPID, NUANCE, EPIC, and IMSERC were also supported by the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-1542205). It also made use of the CryoCluster equipment of BioCryo, which has received support from the MRI program (NSF DMR-1229693). The DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team is supported by Northwestern University, The Dow Chemical Company, and DuPont de Nemours, Inc. Data was collected using an instrument funded by the National Science Foundation under Award Number 0960140. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation–Earth Sciences (EAR–1634415) and U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)-GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). The authors thank Tony Lanzirotti, Matt Newville, Thomas Toellner, and Jiyong Zhao for technical support. This research used resources of the APS, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

© 2021 Northwestern University

See also: New York Times: “How the ‘Wandering Meatloaf’ Got Its Rock-Hard Teeth”

Science News: “The teeth of ‘wandering meatloaf’ contain a rare mineral found only in rocks”

CNN: “This 'wandering meatloaf' chiton has a rare mineral in its teeth”

Science Times: “Rare Iron Mineral Found in the Teeth of a ‘Wandering Meatloaf’ in a First”

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.