The original Penn State University news article by A'ndrea Elyse Messer can be read here.

An iron-rich mineral species that was debunked in the 1920s turns out to be extremely common on Earth, suggesting the existence of a substantial water reservoir on Mars, according to a team of geoscientists from Pennsylvania State University, the Smithsonian Institution, Chevron,and The University of Chicago who carried out studies at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS).

"One of my student's experiments was to crystallize hematite," said Peter J. Heaney, professor of geosciences, Penn State. "She came up with an iron-poor compound, so I went to Google Scholar and found two papers from the 1840s where German mineralogists, using wet chemistry, proposed iron-poor versions of hematite that contained water."

In 1844, Rudolf Hermann named his mineral turgite and in 1847 August Breithaupt named his hydrohematite. According to Heaney, when mineralogists applied the then-novel X-ray diffraction technique a century ago, they declared these two papers incorrect. But the nascent probe was too primitive to see the difference between hematite and hydrohematite.

Si Athena Chen, Heaney's doctoral student in geosciences, began by acquiring a variety of old samples of what had been labeled as containing water. Heaney and Chen obtained a small piece of Breithaupt's original sample, a sample labeled as turgite from the Smithsonian Institution, and, surprisingly, five samples that were in Penn State's own Frederick Augustus Genth collection.

Chen examined the specimens using state-of-the-art techniques, including infrared spectroscopy as well as single-shot and time-resolved synchrotron x-ray diffraction collected at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS 13-BM-C bending magnet x-ray beamline at the APS at Argonne National Laboratory – which is much more sensitive than what was available in the early 20th century! Chen showed that these minerals were indeed light in iron and had hydroxyl — a hydrogen and oxygen group — substituted for some of the iron atoms. The hydroxyl in the mineral is stored water.

The researchers recently proposed in the journal Geology "that hydrohematite is common in low-temperature occurrences of iron oxide on Earth, and by extension it may inventory large quantities of water in apparently arid planetary environments, such as the surface of Mars."

"I was trying to see what were the natural conditions to form iron oxides," said Chen. "What were the necessary temperatures and pH to crystallize these hydrous phases and could I figure out a way to synthesize them?"

She found that at temperatures lower than 300 degrees Fahrenheit, in a watery, alkaline environment the hydrohematite can precipitate out, forming sedimentary layers.

"Much of Mars' surface apparently originated when the surface was wetter and iron oxides precipitated from that water," said Heaney. "But the existence of hydrohematite on Mars is still speculative."

The "blueberries" found in 2004 by NASA's Opportunity rover are hematite. Although the latest Mars rovers do have X-ray diffraction devices to identify hematite, they are not sophisticated enough to differentiate between hematite and hydrohematite.

"On Earth, these spherical structures are hydrohematite, so it seems reasonable to me to speculate that the bright red pebbles on Mars are hydrohematite," said Heaney.

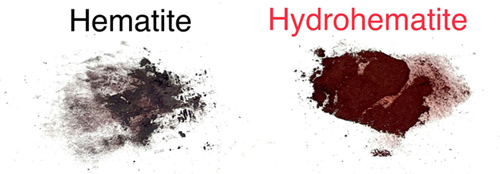

The researchers note that anhydrous hematite — lacking water — and hydrohematite — containing water — are two different colors, with hydrohematite a brighter red.

Chen's experiments found that naturally occurring hydrohematite contained 3.6% to 7.8% by weight of water and that goethite contained about 10% by weight of water. Depending on the amount of hydrated iron minerals found on Mars, the researchers believe there could be a substantial water reserve there.

Mars is called the red planet because of its color, which comes from iron compounds in the Martian dirt. According to the researchers, the presence of hydrohematite on Mars would provide additional evidence that Mars was once a watery planet, and water is the one compound necessary for all life forms on Earth.

A Penn State video about this research can be viewed here.

See: Si Athena Chen1*, Peter J. Heaney1**, Jeffrey E. Post2, Timothy B. Fischer3, Peter J. Eng4, and Joanne E. Stubbs4, “Superhydrous hematite and goethite: A potential water reservoir in the red dust of Mars?,” Geology, published on line 20 July, 2021. DOI: 10.1130/G48929.1

Author affiliations: 1The Pennsylvania State University, 2 Smithsonian Institution, 3Chevron, 4The University of Chicago

Correspondence: * [email protected], ** [email protected]

This work was funded by a seed grant from The Pennsylvania State University Biogeochemistry dual-title Ph.D. program and by U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) grants EAR-1552211 and EAR-1925903. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the NSF–Earth Sciences (grant EAR–1634415) and U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)–GeoSciences (grant DE-FG02-94ER14466). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Copyright The Pennsylvania State University © 2021

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.