The original UCLA Samueli School of Engineering news story can be read here.

UCLA researchers and their colleagues, with data from investigations at two U.S. Department of Energy x-ray light sources including the Advanced Photon Source (APS), have discovered a new physics principle governing how heat transfers through materials, and the finding contradicts the conventional wisdom that heat always moves faster as pressure increases. Their results were published in the journal Nature.

Up until now, that common belief has held true in recorded observations and scientific experiments involving different materials such as gases, liquids, and solids.

The researchers have found that boron arsenide (BAs), which has already been viewed as a highly promising material for heat management and advanced electronics, also has a unique property. After reaching an extremely high pressure that is hundreds of times greater than the pressure found at the bottom of the ocean, boron arsenide’s thermal conductivity actually begins to decrease.

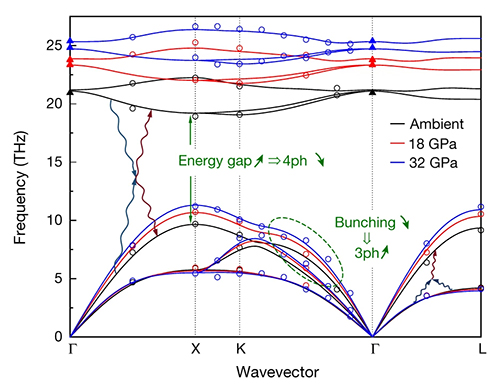

To achieve the extremely high-pressure environment for their heat-transfer demonstrations, the researchers placed and compressed a boron arsenide crystal between two diamonds in a controlled chamber. They then utilized quantum theory and several advanced imaging techniques, including ultrafast optics. To observe and validate the previously unknown phenomenon, the team also carried out pressure-dependent inelastic x-ray scattering measurements (Fig. 1) at the APS X-ray Science Division Inelastic X-ray & Nuclear Resonant Scattering (IXN) Group‘s 30-ID beamline at the APS at Argonne National Laboratory to directly measure the phonon dispersion of BAs, and pressure-dependent x-ray diffraction experiments to verify the crystal phase structure of BAs at the Advanced Light Source (ALS) beamline 12.2.2 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (both the APS and ALS are Department of Energy Office of Science user facilities).

The results suggest that there might be other materials experiencing the same phenomenon under extreme conditions. The advance may also lead to novel materials that could be developed for smart energy systems with built-in “pressure windows” so that the system only switches on within a certain pressure range before shutting off automatically after reaching a maximum pressure point.

“This fundamental research finding shows that the general rule of pressure dependence starts to fail under extreme conditions,” said study leader Yongjie Hu, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. “We expect that this study will not only provide a benchmark for potentially revising current understanding of heat movement, but it could also impact established modeling predictions for extreme conditions, such as those found in the Earth’s interior, where direct measurements are not possible.”

According to Hu, the research breakthrough may also lead to retooling of standard techniques used in shock wave studies.

Similar to how a sound wave travels through a rung bell, heat travels through most materials by way of atomic vibrations. As pressure squeezes atoms inside a material closer together, it enables heat to move through the material faster, atom by atom, until its structure breaks down or transforms to another phase.

That is not the case, however, with boron arsenide. The research team observed that heat started to move slower under extreme pressure, suggesting a possible interference caused by different ways the heat vibrates through the structure as pressure mounts, similar to overlapping waves cancelling out each other. Ahmet Alatas, one of the co-authors of the paper and the person in charge of the HERIX spectrometer at APS Sector 30, said, “Such interference involves higher-order phonon interactions that cannot be explained in traditional harmonic approximation for the common materials. Use of the IXS method to identify the pressure dependent phonon dispersion curve in full Brillouin zone was one of the critical ways to fully explain this ‘anomalous’ behavior from BAs.” Ahmet added, “this kind of research will greatly benefit from the more intense and more stable x-ray beam at the post-APS Upgrade era.”

The results also suggest that the thermal conductivity of minerals can reach a maximum after a certain pressure range. “If applicable to planetary interiors, this may suggest a mechanism for an internal “thermal window” — an internal layer within the planet where the mechanisms of heat flow are different from those below and above it,” said co-author Abby Kavner, a professor of earth, planetary, and space sciences at UCLA. “A layer like this may generate interesting dynamic behavior in the interiors of large planets.”

See: Suixuan Li1, Zihao Qin1, Huan Wu1, Man Li1, Martin Kunz2, Ahmet Alatas3, Abby Kavner1, and Yongjie Hu1*, Anomalous thermal transport under high pressure in boron arsenide,” Nature (published 23 November 2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05381-x

Author affiliations: 1University of California, Los Angeles, 2Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: * [email protected]

Y.H. acknowledges support from a CAREER Award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) under grant no. DMR-1753393, an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship under grant no. FG-2019-11788, and the Vernroy Makoto Watanabe Excellence in Research Award. This work used computational and storage services associated with the Hoffman 2 Shared Cluster provided by UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education’s Research Technology Group, and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by NSF grant number ACI-1548562. This research used resources of the Advanced Light Source, which is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

The Advanced Light Source is a U.S. Department of Energy scientific user facility at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Our mission is to advance science for the benefit of society by providing our world-class synchrotron light source capabilities and expertise to a broad scientific community.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.